What Rashi Taught Me About Antizionism

How a thousand-year-old commentary helps us understand the world’s obsession with Israel.

(Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki, better known as Rashi, the great biblical commentator and illuminator.)

What if we’ve been thinking about this all wrong?

What if we’ve been fighting pernicious anti-Jewish lies for so long that we actually lost the thread?

What if antizionism is not antisemitism – what if we got it backwards?

Last week, we began the yearly Torah reading cycle anew, and, on the very first page, on the very first line, there is a comment from Rashi, the great 11th century Torah commentator, that should give us all pause.

In the margins besides the words “in the beginning,” Rashi writes:

“IN THE BEGINNING — Rabbi Isaac said: The Torah, which is the Law book of Israel, should have commenced with the verse (Exodus 12:2) “This month shall be unto you the first of the months” which is the first commandment given to Israel. What is the reason, then, that it commences with the account of the Creation? Because of the thought expressed in the text (Psalms 111:6) “He declared to His people the strength of His works (i.e. He gave an account of the work of Creation), in order that He might give them the heritage of the nations.” For should the peoples of the world say to Israel, “You are robbers, because you took by force the lands of the seven nations of Canaan”, Israel may reply to them, “All the earth belongs to the Holy One, blessed be He; He created it and gave it to whom He pleased. When He willed, He gave it to them, and when He willed, He took it from them and gave it to us.”

Had he written this last year, it would still have been profound, but he wrote it over 900 years ago… 800 years before the State of Israel would even be founded.

What did Rashi understand that we don’t? How was he able to see so far into the future that he could predict the arguments of modern antizionists better than we can?

For context, Rashi lived from 1040-1105. Those were certainly interesting times, both in his native France and in Europe broadly.

He was 26 years old when William the Bastard conquered England, and he was 55 when Pope Urban II declared the first crusade to liberate the holy land.

Rashi himself knew the crusades intimately. The stories vary, but there are many legends about why Rashi and his community were saved from that crusade.

The other Jews of Europe, however, were not.

We rarely think of Rashi as a historical observer, but perhaps we should if we are to understand how he could have anticipated antizionism.

As a Jew, Rashi might have understood the history leading up to the crusades as follows.

In 70 CE, Rome exiles the Jews.

In 380 CE, Rome adopts Christianity, making the Holy Land Christian.

In 638 CE, the forces of Islam capture the Holy Land, making it Muslim.

In 1095 CE, the forces of Christianity invade the Holy Land in order to return the land to… its Christian roots.

(Map of the First Crusade. The crusaders murdered 25,000 Jews from the great Jewish communities of Speyers, Worms and Mainz on their way to liberate the Holy Land)

Rashi was 55 years old when the Crusades began. He had spent 55 years of his life mourning the destruction of the Jewish Temple, fasting for one day in each of those years to remember the sorrow and the anguish the Jews felt when our Temple was destroyed and we were sent out of our Holy Land.

And then, in his 56th year, when the Crusades began, he would have seen these men, marching to that same Holy Land, ostensibly to liberate it, riding into Jewish communities and massacring their inhabitants.

In their desperation to liberate the Jewish Holy Land, the Crusaders liberated many Jews from their lives.

But why? Why kill all of these Jews who haven’t been to the Holy Land in centuries?

The traditional answer has always been antisemitism, more or less.

The Christians hated their Jewish neighbors and the Crusades were as good an opportunity as any to get rid of them.

But maybe not. Maybe there is a more sinister connection between the ideology of the Crusade and anti-Jewish violence that Rashi alludes to. Maybe Rashi’s experience with the Crusades gave him insight into the mind of the Crusading Jew Hater.

According to Rashi (quoting Rabbi Isaac), the nations of the world call us “robbers,” because we stole the land from the 7 nations of Canaan, but that’s not exactly the truth.

They do call us robbers, for sure, and they do say that we stole the land, absolutely – but no one ever cites the Canaanites.

There is no “Nakba Day” for the Hittites and the Perizzites, and no one talks about the cultural erasure of the Jebusite identity. And the Amorites? They get no play in today’s world of virtue signaling. People care less about the Canaanite nations than they do about the actual genocides happening in the world today.

So what is Rashi doing here?

I must confess – I have been a little bit dishonest with you.

This teaching does not come from Rashi; it comes from Rabbi Isaac, who Rashi is quoting.

However, our chronology still works, because Rabbi Isaac was Rashi’s father.

So, when we read this line, we should imagine Rashi not as the teacher, as we usually do, but as the student.

For whatever reason, I have always imagined that this teaching happened like this:

A bearded man and his son are sitting in the house of study, learning this parasha together.

A few Christians come by and sneer, “look at the Jews, studying a book they think was promised to them, learning laws for a land they think was promised to them, pretending they’re so much better than us. Doesn’t that book say what we already know, that you stole that land? You stole that land like you steal everything, because you’re all greedy Jewish thieves.”

The bearded man, with recourse to nothing but wisdom, looks at his young son and says,

“You see? That is why the Torah begins right here, with the creation of the world. It should have started with the first law, so why start here with creation? Because people like that will always come to us and say things like this. They always have, and they always will.

But we know – G-d created the whole world, and He decides who gets what. We lived in Israel once, and we will live there again, because G-d has always kept His covenant with us.”

At the time when Rashi learned this from his father, the nations of the world were confident in their ridicule.

The Jews had been exiled for 900 years – who would seriously believe that G-d was still keeping faith with the Jews?

When Rashi learned this from his father, the nations of the world were confident in their ridicule. The exile would have been proof positive that our covenant was broken and our relationship to the land void.

But our enemies, according to Rabbi Isaac and Rashi, do not claim that our covenant was broken – they claim that we never had one to begin with.

But why? Why make such a big deal about how the Jews got the land anyways? It is not as though the medieval nations of Europe were opposed to conquest, that was the whole point of the crusades to begin with!

Perhaps the answer lies in Rabbi Isaac’s quiet, devastating response:

“Israel may reply to them, “All the earth belongs to the Holy One, blessed be He; He created it and gave it to whom He pleased. When He willed He gave it to them, and when He willed He took it from them and gave it to us.””

This answer is remarkable.

Firstly, it accepts exile, not as an evil imposed on the Jewish people by others, but as a condition that was divinely approved. Living at such a precarious time for the Jewish people, this answer reflects the tremendous depth of the Jewish character – we accept our exile.

We could just as easily point the finger at the Romans, or the Arabs, or the Crusaders, or the Ottomans, or the British, and we could say, “Robbers! You are all robbers! You have stolen our land from us!”

But we don’t.

We accept our exile as a condition of G-d’s plan. We did that in 1948, Rashi and his father did it in 1100 — and we still do it today.

But in our acceptance is hope, and in our hope, there is prophecy.

This response is prophetic – it predicts our return to the land of Israel 800 years before it happens.

Rashi and his father lived at the midpoint of Jewish exile — nine centuries after the Temple’s fall, nine before the State’s rebirth.

But even if that was not prophetic enough – they go on to predict the exact nature of the antizionist critique – land theft.

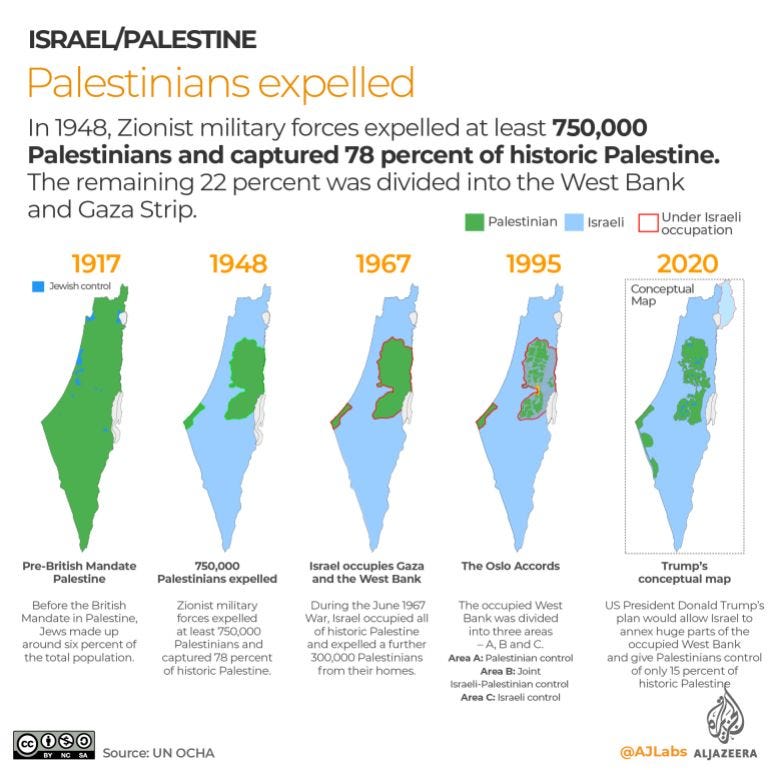

(Graphics displaying our robbery of the land.)

(Protests against our ownership of the land outside of a synagogue in Canada.)

(The modern version of what Rashi anticipated. There are whole organizations, like Visualizing Palestine, that are dedicated to creating graphics that show ‘this land theft.’)

Most people believe that modern antizionism is a response to modern Zionism, as the names would imply.

But what if that’s not quite right?

What if antizionism is actually as old as the Crusades, if not older?

If we are to proceed, we need a definition of antizionism. I think this one will do:

Antizionism is an ancient and obsessive impulse to deny that Jews have any meaningful connection to the Land of Israel.

If we are to understand the dynamics of antizionism, which has quickly become one of the major ideological movements of our day, we need to broaden our conception of why so many people, and so many Europeans especially, obsess over Jews and Israel.

We must look at Rashi’s wisdom and consider what the medieval crusaders of his day have in common with the modern antizionists of our own.

According to Rashi, the peoples of the world look at us and say, “You are robbers, because you took by force the lands of the seven nations of Canaan.”

Our initial assumption was that the peoples of the world want Israel to deny this claim and say, “no! We are not robbers, we did not steal the land…”

But what if we are reading that wrong too?

What if the world expects us to brag? What if they expect us to say:

“Yes! We are robbers! We took the lands of the seven nations of Canaan by force, and we are damn proud of it. Here are the names of the brilliant burglars who helped us steal the land.”

After all, the Crusades are only 30 years after the Norman conquest (robbery) of England, a moment in which William the Conqueror sailed from Normandy, invaded England, executed 90% of the native nobility, and established an occupation government that has remained there ever since.

The Normans are still tremendously revered today, and they are revered precisely because of their conquest and theft.

He is “William the Conqueror” not “William who Had a Legitimate Claim ordained by G-d” – and he is revered for it.

And the biggest irony is that the Normans were not even native to Normandy.

The word “Norman” comes from “Norseman” because, originally, the Normans were Vikings who came down and conquered Normandy, gaining official recognition of their conquest in 911 C.E.

Historical memory about land stealing is so short that within 150 years of their conquest of Normandy, everyone had forgotten that they were originally Vikings.

Normandy is still named after the Vikings who stole the land from the natives, and the English nobility is still ruled by their descendants, but no one calls them robbers.

Robbery, specifically land theft, is the way of the world.

In fact, the only nation that has some claim to their land that is not rooted in land theft is Israel.

Our claim, as Rashi explains, is fundamentally religious. G-d made the heavens and the earth, and He decides who gets what.

In the 11th century, he decided that the Holy Land should be ruled by Muslim conquerors. For a few years between 1095 and 1400, He decided it should be ruled by Christians. Between 1500 and 1917, He gave it to the Ottomans, and, after that, to the British.

In 1948, He chose to give it back to us, and He could change His mind at any time, because the whole world belongs to Him.

If we are in the land, according to our argument, it is not due to military conquest – it is due to Him.

The answer is as simple as it is beautiful.

But it’s also infuriating.

There is nothing more infuriating than someone who has made peace with their situation and takes responsibility for it.

This is the quiet confidence of Zionism.

Our conviction that G-d promised us that land is absolute, so the vicissitudes of history are irrelevant – we’ll be there when we’re meant to be there.

And this confidence goes back to Rashi and long before him.

It is a confidence that comes, ironically, from having a relationship with the land rooted in something other than conquest. There is something about Jews and the 8500 square miles of Israel that is inseparable.

Zionism is that connection.

Zionism is this wholly unnatural belief that the Jewish people’s connection to the land goes beyond conquest; that is why the attack against us is always the same.

In Rashi’s day, the attack was meant to shame us for having lost the land we claim was promised to us by G-d.

Because if G-d did promise it to us, then it was not stolen. If He did not promise it to us, we are robbers.

But, if He did promise it to us, we would not have been exiled, so, therefore, we must be robbers.

Which would make us like everyone else – except that we are the only people who do not relish the title of conqueror.

There is no “Joshua the Conqueror” or “David the Great” in Jewish culture. Our heroes are revered for other things, like Rashi, who is remembered for his scholarship.

In this one gloss on one line of Torah, Rashi explains 1800 years of antizionism, from the Christian Romans to the modern SJP.

For 2000 years, the shame of our exile denied the legitimacy of our claim.

But when the Jews returned to the land, and built a community, and then an army, and then a state, all of the sudden, Rashi and his father were vindicated.

Zionism, the basic understanding of Jews’ historical connection to Israel, is the manifestation of G-d’s eternal covenant with the Jewish people.

Our connection to the land, for the 2000 years we were waiting to return, fulfilled our contractual obligation, and our return to the land fulfilled G-d’s.

In these past 2000 years, people like Rashi and his father have kept faith with our divine connection to the land, even when there was no reasonable hope of return.

We always associate the Zionist dream with Theodore Herzl, but maybe we need to start expanding our view.

Because the Zionist dream is at least as old as Rashi’s father. And, if I’m being honest, I think the Zionist dream probably goes all the way back to Moses, but that we’ll have to save for another essay.

(Yom Kippur 1967)

~

As always,

Spread Love, Spread Light,

Am Yisrael Chai