The Tents of Jacob:

A Reflection on Jewish Community

This week’s Torah portion is one of the strangest in the entire Torah.

Parashat Balak tells the story of an antisemitic king named Balak who hires a sorcerer named Bilaam to curse the Jewish people.

However, when all is said and done and Bilaam is ready to curse the Jewish people, out of his mouth escapes a blessing, and not just any blessing, but perhaps the most beautiful and prophetic blessing in the entire Jewish Liturgy:

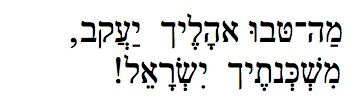

“Mah Tovu, Ohalech haYaacov, Mishkenotecha, Yisrael.”

“How wondrous are your tents, oh people of Jacob, How magnificent are the places where you dwell, oh people of Israel”

No matter how many hundreds of times I sung this song as a child, I never understood what it meant until I became a teacher.

And I did not understand that I finally understood this prayer until last Shabbat.

Last Shabbat, I had the extreme pleasure of attending my 10 year camp reunion.

We drove out to Simi Valley, where Brandeis Bardin is located, the security guards checked out IDs and license plate numbers, I drove slowly down Peppertree Lane flanked on both sides by great and wise trees, I got out of the car, and I returned to a peaceful paradise of my youth.

Camp, for me and for many other young Jews, was not a home away from home for us – it was a second home, a special home, a communal home.

As mainstream American culture has become progressively more isolated and lonely, camp culture has remained markedly integrated and communal.

It is a place where people live together, eat together, sing together, play together, fight together, learn together, and, most importantly, camp is a place where people perform acts of hijinks and tomfoolery together.

Camp is a place to be together.

So after quite a lonely year for the Jewish people, the togetherness of camp provided a much needed reprieve.

Returning to the camp of my youth renewed my soul with an ancient conviction, the kind which one only gets upon seeing Jewish children dressed in white to greet the sabbath bride before inevitably covering their beautiful clothes in a motley combination of grape juice and mud.

The scene was the same as it had been my first Shabbat there back in the antediluvian days of 2007.

Children dressed in white, holding hands, singing shabbat songs, chanting Jewish prayers, whispering jokes to one another when they think no one is looking – nothing has changed in the 17 years since the first time I saw a Kabbalat Shabbat.

But when I came back to our camp after many years away, I saw the could, for the first time, see the camp as an outsider, as an observer.

I could look upon our spiritual dwelling place from above, as Bilaam had when he saw the congregation of Israel spread out before him.

Mah tovu, ohalecha yaacov.

How lovely are your tents, oh people of Jacob.

But what is it about our tents that makes them so lovely?

It is that they are filled with the sound of child’s play. Our camps, our synagogues, our schools, every communal organization that Jews build is designed around the children.

Every shul has a playground, and every ceremony has candy for the kids.

We, the Jewish people, love kids.

We protect our children, we cherish our children, and we teach our children.

This is who we are; this is who we always have been.

We are child-rearers.

Since the days of Abraham, the Jews have distinguished ourselves by our unparalleled devotion to our children.

Despite having hundreds of servants and tremendous wealth, Abraham still made it his priority to teach his son the proper way to live.

How many of our modern day billionaires can say the same?

Moses spent 40 years in the desert, not only teaching Torah to the people, but also printing Torah scrolls by hand to ensure that the grandchildren of the Jewish people would not lose access to our holy teachings.

Rabbi Shimon ben Shattach established rural schools to teach every male Jewish child how to read 1800 years before the invention of the printing press.

Literacy is an issue that is very close to my heart because I was borderline illiterate going into third grade. If I did not learn how to read by the end of it, there was a good chance that I would never have been able to read.

So my dad spent every night that summer teaching me how to read, and, without his help, I would not be writing this essay that you are reading today.

My dad showed me devotion. He showed me that there was nothing more important to him than that I should learn the things I needed to learn in order to have a good life.

That same devotion permeates every element of Jewish child-rearing.

Before I began teaching in a yeshiva, I expected the Yeshiva to be somewhat drab and dower – it was the opposite.

While the students were dressed in black and spent 13+ hours a day in school studying books in ancient languages that no one speaks any more, the atmosphere was actually quite fun-loving and free.

Unlike my previous experiences teaching secular American high school students, the Yeshiva students were carefree and mentally healthy.

Which, in 2024, is a miracle.

My students laughed, they played pranks on one another, they even organized an end-of-the-year paintball excursion. (which I absolutely participated in)

Although they came from a different Jewish background than me, they showed me that, ultimately, our values are the same.

Shlomo Bardin, the founder of Brandeis-Bardin and one of the originators of Jewish camp in America, once described camp as “a laboratory for living Judaism.” It is a place for Jews to live Jewishly, and part of living Jewishly is experimenting and learning about new ways of being Jewish.

(The Trees Shall Remember Your Being Here is an old camp saying whose wisdom is too deep to even try to explain.)

The Yeshiva is, in many ways, the exact same thing, just “with a slightly different level of text study,” as my old boss recently said.

While the Yeshiva and the Pluralistic Jewish Summer Camp may look like very different tents, they are both equally beautiful as dwelling places of the Jewish people.

That, I believe, is the true beauty of this week’s Torah portion.

Even a hateful antisemite, hell-bent on destroying the Jewish people at all costs, cannot deny the beauty of the tents we built to teach our children.

The blessing begins with the question, “Mah tovu?”, “How lovely are the tents of Jacob?”

I always thought the question was rhetorical, but now I am beginning to think it is one which actually begets an answer.

How lovely are the tents of Jacob?

Lovely enough that we have been building them the same way for 3000 years, and they are no less cherished and beautiful than they were then.

Spread Love, Spread Light,

Am Yisrael Chai

~

Dear Reader,

We are trying out some branding/merchandising options to financially support this work, so take a look and let me know what you think!

Wonderful. Masterful.