No Room for a Jew in the Revolution:

What One Battle after Another taught me about our current political climate

(Author’s Note: We are living through a time in which Jewish homelessness — physical, political, and existential — is no longer metaphor but lived reality. Everywhere we turn, the ground feels less stable, and the signals of increasing political violence are impossible to ignore. This piece began as a reflection on a work of art, but it has revealed itself to be something closer to a mirror: a way of seeing our current condition through the story of another battle, another exile, another moment when Jews were asked to survive without a place to stand. I am publishing it now not as a review, but as a reminder of where we are, and what we may be walking into.)

There is no room for a Jew in a war between radical Marxists and Neo-nazis.

That was my first thought watching One Battle after Another.

The film tells the story of a radical group of leftist revolutionaries, The French 75, and the white supremacist who is hell-bent on catching and destroying the organization’s leadership.

The movie is highly entertaining, with lots of laughs and excitement, and I highly recommend it.

Like everything made these days, the film is too long. The plot drags at times and gets overly involved in itself, but it is still one of the better movies you will see this year, even if it is not one of Anderson’s best.

However, beneath the surface lies a much deeper story about political violence and those who justify it.

A Brief History Lesson

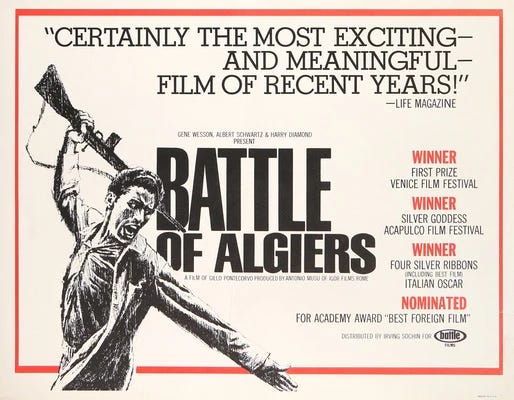

The most important film you’ve probably never seen is The Battle of Algiers (1966). It is an Italian-Algerian film that tells the story of Ali La Pointe, leader of the FLN, the radical nationalist organization that led the resistance against the French colonial authority, and the colonial police who are determined to catch La Pointe at all costs.

Understanding The Battle of Algiers is essential to understanding how Anderson frames his revolutionaries, and how those revolutionaries resemble the would-be revolutionaries of today.

It is the epitome of a resistance film and a must-watch for any anticolonial film studies major, and the influence on One Battle after Another could not be clearer.

The two sides in The Battle of Algiers could not be more clear: black native Algerian resistance fighter vs. white colonial French tyrant. The same is true in Anderson’s film, with the beautiful and brave Teyanna Taylor squaring off against the lock-jawed WASP drill sergeant played by Sean Penn.

If you want to understand the relationship between radical Islamism and radical Marxism, you need to understand the Algerian Revolution.

The Algerian Revolution brought radical French leftists and radical Islamic nationalists together.

Writers like Foucault, Fanon, and Sartre all wrote about the heroism and the humanity of revolution.

They cared more about the fulfillment of their ideas than the lives that would be lost.

Fanon, the most vocal, wrote:

“And it is clear that in the colonial countries the peasants alone are revolutionary… The starving peasant, outside the class system is the first among the exploited to discover that only violence pays. For him there is no compromise, no possible coming to terms; colonization and decolonization is simply a question of relative strength.”

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

(Still of FLN fighters from The Battle of Algiers.)

The Battle of Algiers, both the historical event and the movie, gave rise to a new kind of man, a kind of man that the radical European mind became obsessed with: the uncompromising anti-colonial radical.

And that man is sexy.

Just wait until you see everyone dressed up as “Bob” (Leo’s character) on Halloween. Or ask any of Luigi Mangione’s fan girls.

In a world with fewer and fewer male role models, the man who is willing to dedicate his entire life to the violent pursuit of his cause has tremendous sex appeal.

As you watch the film, the appeal of the revolutionary grows within you, especially as you see the righteousness of their cause and the stupidity of their enemy’s cause.

There is something tremendously appealing about revolution and violence, especially for young people.

But what happens when revolution becomes the only moral language left — and Jews don’t fit the script?

Revolutionaries and Israel

Since the Battle of Algiers and the eponymous film, the revolutionary has remained a mainstay in the cultural zeitgeist, even as colonialism collapsed all around the world.

Except, according to the post-colonial left, for Israel – they believe Israel is the last colonial country remaining.

And so, for anyone who is cut from the same cloth as Ali La Pointe or Angela Davis, Israel becomes the final frontier in the eternal war against Colonialism.

Israel and Jews are never mentioned in the film, which was a huge breath of relief. The film exclusively deals with immigration related issues. In the world of the movie, those two issues have nothing in common.

But, in the world of today, they do.

Virtually all radical leftist movements are virulently antizionist. While Israel has absolutely nothing to do with ICE, there are still organizations like La Raza por Gaza that do everything they can to bring those two issues together in people’s minds, or people like Zohran Mamdani, who believe NYPD violence is caused and inspired by IDF.

“When the boot of the NYPD is on your neck, it’s been laced by the IDF!” (Zohran Mamdani, September 2023)

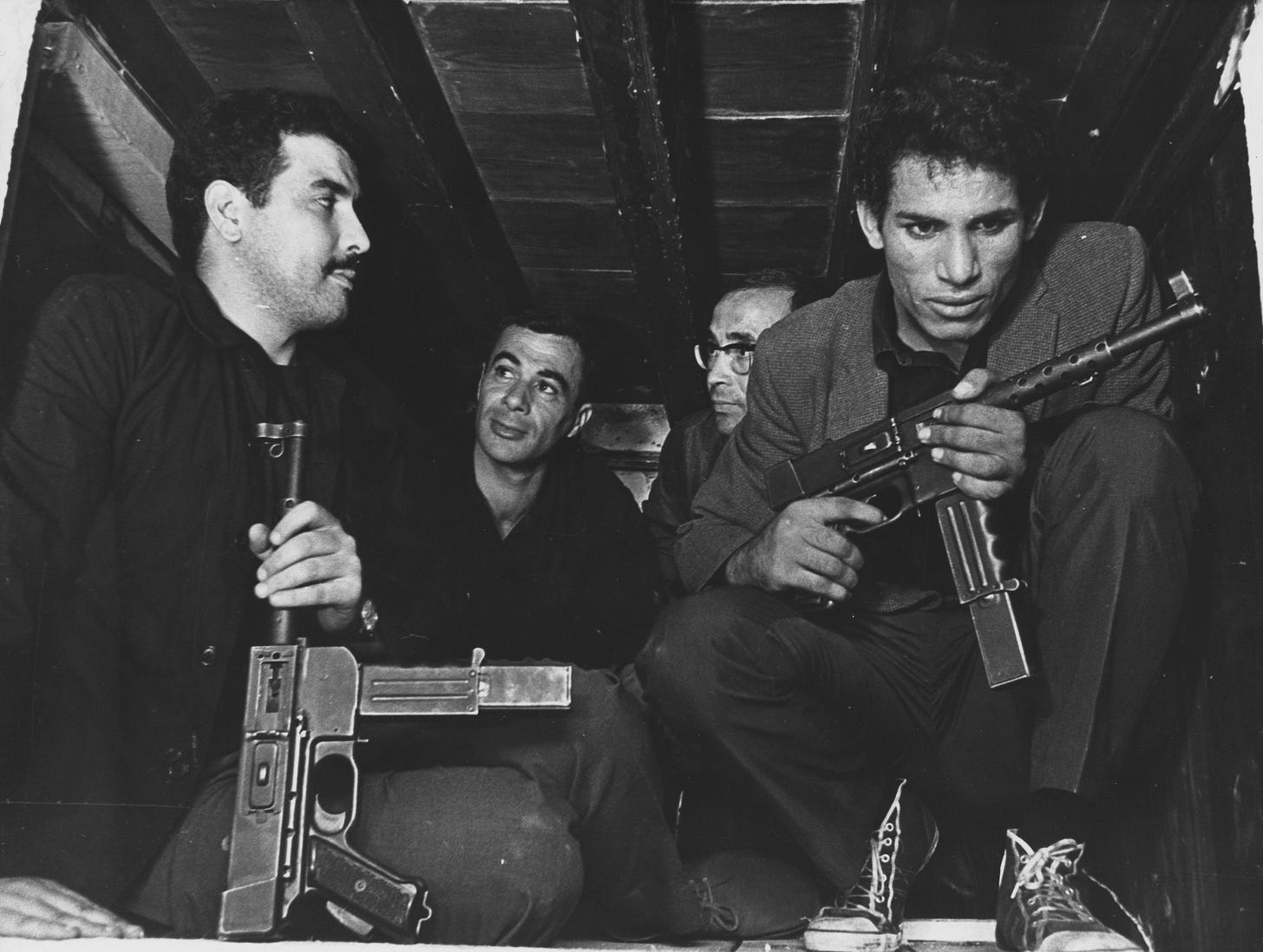

(An image published by Within Our Lifetime on November 16, 2023 demonstrating the location of Zionist organizations to target.)

Since everyone wants to be a revolutionary, and the revolution is anti-Israel, you must be an antizionist to be a revolutionary, it is that simple.

Sadly, I know a lot of people, kids really, who threw away their Jewish identity for their revolutionary identity.

In 2025, one of those identities has sex appeal, and one of them doesn’t.

One Battle After Another has its finger on the pulse of American political bitterness. Membership in radical organizations and participation in political violence is way up on the left, and membership in white nationalist groups and participation in political violence are way up on the right too.

We, the Jewish people, as always, are stuck in the middle.

You will never be revolutionary enough to make people forget you’re a Jew.

Just ask Leon Trotsky.

1968 Reprise

Teyana Taylor’s character, Perfidia Beverly Hills, is a young revolutionary raised by revolutionaries. She is the living embodiment of the revolution.

(Still of Perfidia Beverly Hills from One Battle after Another.)

After her initial revolutionary forays, she is apprehended, but she eventually manages to escape.

In many ways, her character resembles Assata Shakur, the black revolutionary who killed a New Jersey State Trooper in 1973, but she escaped from prison in 1979 and lived out the rest of her life in Cuba.

She died less than a month ago, on September 25, 2025.

Assata Shakur was the last major revolutionary figure from the radical black power movement of the 1960s.

Like the other revolutionaries of that era, Angela Davis, Huey Newton, and Kathleen Cleaver, to name a few, she carries an incredible amount of cultural significance.

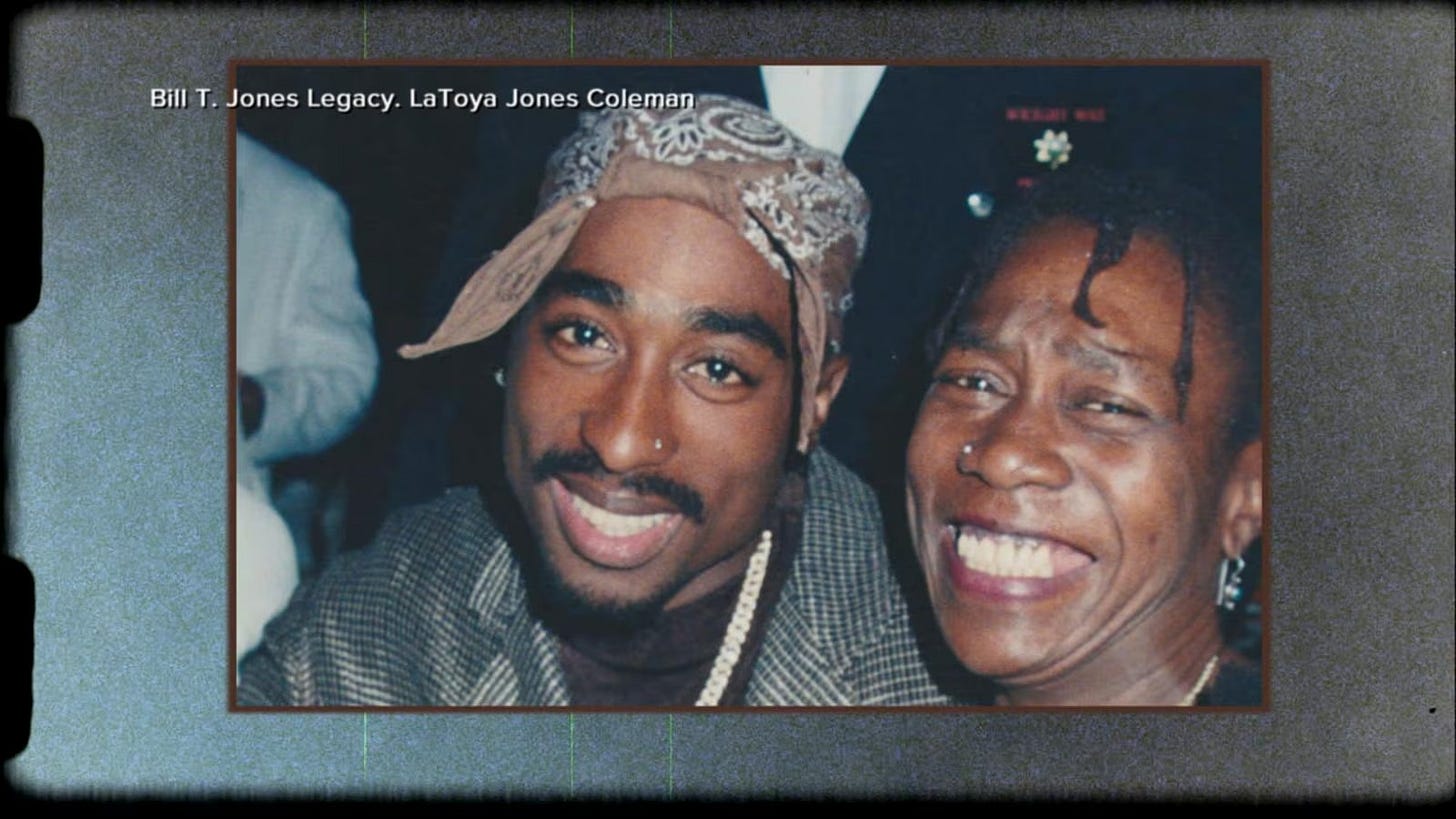

If her name sounds familiar, that might be because she was godmother to the world-renowned Tupac Shakur.

One of the ideas played with in the film is the generational transmission of the revolution from mother to daughter.

While the revolutionary fervor of 1968 and the years that followed died off, there was still a reservoir of revolutionary passion in the families that carried it.

And, of course, in the universities whose professors never abandoned their dreams.

The world of 2025 has been looking eerily similar to 1968. There has been mass political unrest, university chaos, building seizures, and political assassinations.

This film may give us some insight into why that is.

The Revolution This Time

The revolution of the 1960s failed, and the revolutionaries of the 1970s and 80s went into hiding, but their ideas never disappeared.

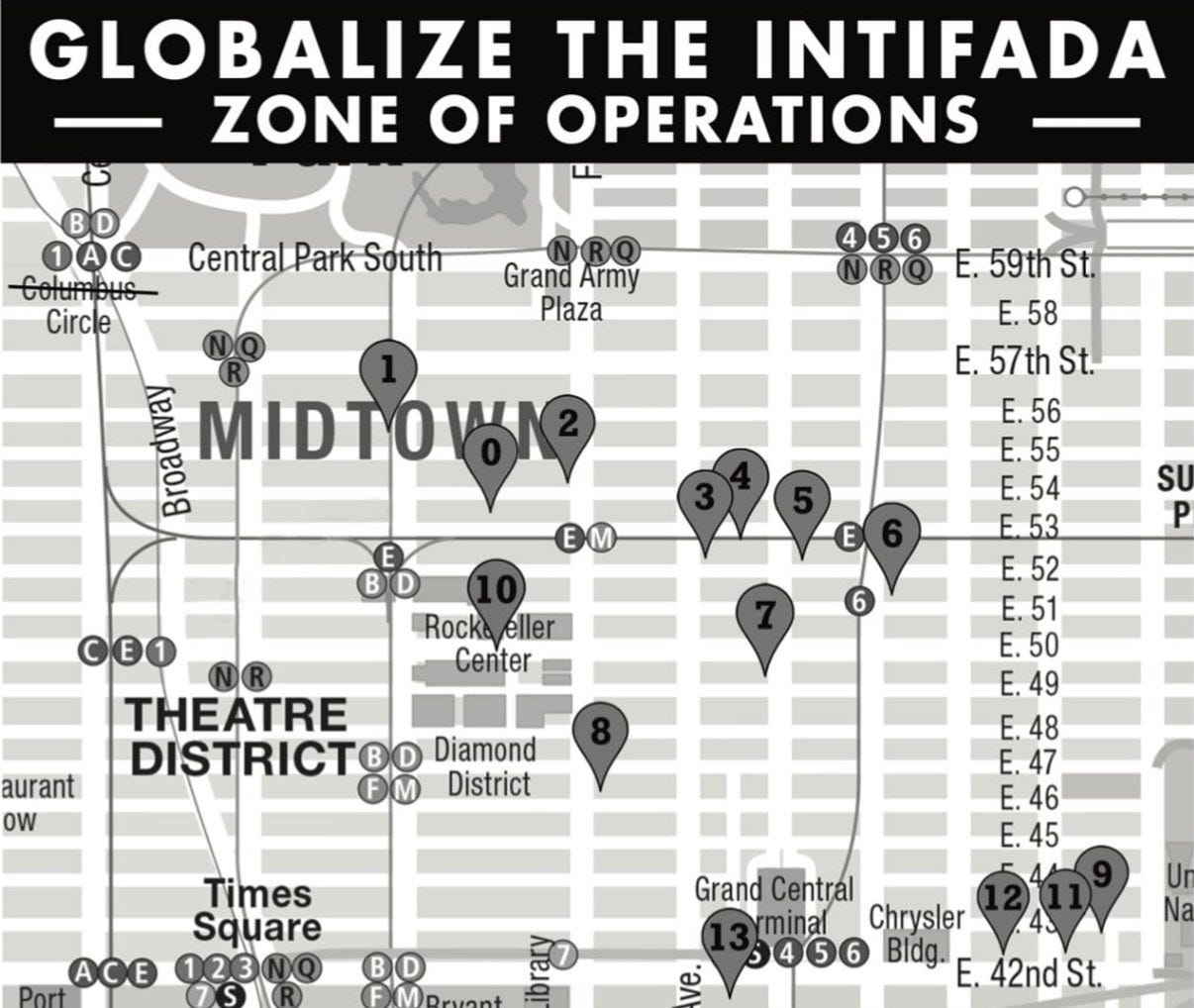

The ideas of revolutionary consciousness and revolutionary violence, first expressed by the New French Left and later appropriated and adapted by black radicals, were perhaps best expressed by the revolution’s only begotten child, Tupac Shakur.

Tupac is misunderstood by almost everyone, and I am certainly no more capable of understanding him than anyone else. But two things about Tupac are undeniable: his literary skill and cultural influence were second to none.

(Tupac Shakur)

If one is to understand our current cultural climate, one must understand rap music, and if one is to understand rap music, one must understand the genius of Tupac Shakur.

Tupac used lyrical storytelling to portray people, long despised by society, in their humanity and in their grace. His music brings empathy to the prostitute, compassion to the single mother, and understanding to the thug. One does not have to like his music to recognize the magnitude of its impact.

His music was violent, and one certainly would not be wrong to say he glorified violence. The picture he painted of himself was a variation of the warrior poet. And all of us poets dream of being the warrior poet because the warrior poet is the living embodiment of his passion. But Tupac was something more. Tupac was the thug poet, the pirate poet – the revolutionary poet.

Unfortunately, most rappers lack the skill and nuance of Tupac, so much of the rap that has followed has glorified violence for violence’s sake, but Tupac was sincere, and his sincerity allowed many people to relate to these struggles even though they had nothing in common with them.

These are the first two verses of “Dear Mama,” one of Tupac’s most revolutionary songs. In it, he expresses gratitude, pain, guilt, anger, self-justification, and much more.

Excerpt from “Dear Mama” by Tupac Shakur

When I was young, me and my mama had beef /

Seventeen years old, kicked out on the streets …

And even as a crack fiend, Mama /

You always was a black queen, Mama /

I finally understand …

There’s no way I can pay you back /

But the plan is to show you that I understand /

You are appreciated.

Verse 2 is an especially powerful expression of the pain of growing up fatherless, the experience of brotherhood in a gang, and the ultimate justification of violence due to necessity.

(Tupac and his mother, Afeni Shakur).

Or, as Lenin would say, the ends justify the means.

If Assata Shakur was the last radical of her generation, then perhaps Tupac was the first of his.

Tupac was weaned on revolution, and he gave birth to a whole new kind of consciousness, a rap consciousness, that glorified and justified violence. Meaning, the people who listen to Tupac, and the people who listen to artists who were influenced by Tupac, develop a new attitude and relationship with violence. Where most people despise violence by nature, one who has been acculturated in the rap world may have a very different relationship with the idea of violence.

This is not to say that all rap music promotes violence or that rap music is inherently violent by nature. You would be hard pressed to find a bigger defender of rap music than I, but, as a major consumer of rap music, I am well aware of the kind of consciousness it cultivates in its listeners.

It is a kind of quasi-revolutionary consciousness – the truly revolutionary consciousness only justifies violence insofar as it supports the revolution, but, because the rap consciousness posits an eternal oppressor-oppressed dynamic, far more violence is justified because even random acts of violence, like robbery and murder, are seen as anti-establishment and therefore beneficial.

Of course, most people who have been influenced by this music are passive fans, and, whatever the music says, they are still averse to violence.

But what happens when that quasi-revolutionary consciousness meets emotionally extreme political unrest?

What happens when a generation of people with this rap consciousness start seeing their friends’ parents getting abducted by ICE agents? What happens when they start seeing national guard officers in the street? What happens when they are bombarded with footage from Gaza telling them Israel is annihilating babies with laser beams?

In the words of the bomb man, “boom.”

When this quasi-revolutionary consciousness mixes with political unrest spread virally on social media, dangerous things start to happen.

The film is discomfortingly prescient in that way. While not explicitly about any of the actual events of the past five years, we can see the similarities plainly. Political violence is on the rise. When one sees cities with masked protestors and riot police, it is hard to not think of 2020. When one sees unhooded Klansmen, it is hard not to think of 2021. When one sees college kids smashing up buildings, it is hard not to think of 2024.

Let us hope that this is wrong, but the film does seem like an omen for what is to come. Once upon a time, I might have looked forward to that as I had my own revolutionary aspirations.

But, like Trotsky, I have learned: there is no room in the revolution for a Jew.

(Leon Trotsky and Ze’ev Jabotinsky. Two of the most brilliant Jewish minds to come out of Tsarist Russia. One was a communist revolutionary, and one was a Zionist revolutionary.)

(A note in closing: In 2025, the feeling of Jewish homelessness is no longer theoretical. We are watching the political extremes grow louder and more violent, each claiming moral purity even as they court bloodshed. And once again, Jews find ourselves with no camp that wants us, no revolution willing to make room for us, no assurance that political chaos will not land on our doorstep. This film is not prophecy, but it is a warning: when the world divides into the righteous and the damned, the Jew is always asked to choose a side that will never choose him back.)

~

Spread Love, Spread Light,

Am Yisrael Chai

Ted, thank you for this essay. I wish you’d been sitting near me while I watched One Battle After Another. And yes, The Battle Of Algiers should be required watching for anyone interested in the Middle East — especially as it relates to Israel, and perhaps as you’ve shown in this essay, for anyone who wants to understand what’s happening today in the US and Europe.